Aphrodite 80 (unfinished)

Matthew Richardson

The ongoing and mutating experiences and developments of Covid can easily make us feel we are living in a fiction devised by the British writer JG Ballard. The term ‘Ballardian’ entered the vernacular a good while back, and citesdystopian man-made landscapes and events and the psychological effects of technology as key conditions of the term. The idea is often attached to specific visual motifs - motorway flyovers, multi-storey car parks, abandoned modernist buildings, empty swimming pools - and appears to be fixed by a trilogy of novels he wrote in the 1970s, all tied fairly particularly in content to the time in which they were written - High Rise, Crash and Concrete Island. But these Ballardian tropes seem to me to limit the range of his work. He also created surreal flooded future landscapes of London, claustrophobic crystalizing jungles, and a vast output of dark, funny, short stories that are vignettes of characters in indeterminant space and time, grappling with technologies that often misbehave and break down.

Considering Ballard’s huge output of short stories and novels and the very visual nature of his writing, it is maybe surprising that his work has not been adapted into films more often. Or maybe not? The structure of Ballard’s narratives are oddly plotless, he seems to set up a location and situation and waits to see how characters respond. Cinema needs a good plot to keep us hooked with cinematic peaks and troughs. His characters are enigmatic and dialogue is functional. We want to empathise with our characters! The three best known films of his work are Crash(David Cronenberg, 1996), Empire of the Sun (Stephen Speilberg, 1988) and High Rise, starring Tom Hiddleston (Ben Wheatley, 2016). Empire of the Sun is probably the most widely known, and the film that took JG Ballard into the mainstream. It is different from the rest of Ballard’s output in that it is semi-autobiographical, depicting a childhood in Shanghai and his feral survival in a Japanese prison camp during WW2. Perhaps it is the fact of a ‘known’ world depicted, a history understood that allows an audience access to the narrative? Unlike the written word, film pins down images that as text are uniquely personal and created in a reader’s mind.

The aspect that feels to me most interesting about Ballard’s writing is the way he deals with time and in this sense, the connection of his narratives to cinema is really interesting. ‘Ballardian time’ has a particular quality - a kind of moving stillness and claustrophobic airlessness. Ballard’s narrative time doesn't really describe past events, or use flash backs, or conversely look towards a distant future. Ballardian time exists in the continuous present, or as Ballard would put it, somewhere in ‘the next five minutes’.

In an art context, this sense of time in Ballard’s work has been the catalyst for a number of artists and artworks, including a filmic combination of The Night of the Hunter and The Crystal World (2013) by Pia Borg and the film J.G(2013) by Tacita Dean referencing Ballard’s short story The Voices of Time.

For the last couple of years I have been working on a project titled The Para-Illustration of JG Ballard, making work that explores the space between the literary and visual. I have been spending a lot of time at the British Library looking at Ballard’s original manuscripts and using these as blueprints to construct objects, images and films. Ballard’s manuscripts are typed and crossed through with changes and deletions – and I am looking for ‘lost’ and ‘hidden’ content and seeing how these ghosted and fragmented narratives might translate.

In the late 1960s Ballard wrote a fantastic set of short stories collected together as Vermillion Sands. Vermillion Sands is a kind of non-place, in a future time, but not too far from a future-dilapidated coastal resort like Palm Springs, California, a place populated by wealthy yet forgotten and disaffected actors, actresses and artists. I love the atmosphere and setting of these stories – the warm dusk, the slow action, and the strange technologies (sound sculptures, poetry-making machines, sentient houses, etc) that make life worth living for the inhabitants.

Chris Beckett, the archivist of the JG Ballard archive at the British Library writes of the characters in Vermillion Sands, as ‘hybrid caricatures, dark blends of notoriety and neurosis, part new-world Hollywood and part old-world European decadence: with names such as Leonora Chanel, Emerelda Garland, Lunora Goalen, Hope Cunard, Lorraine Drexel, Raine Channing, and Gloria Tremayne’. Roger Luckhurst, in The Angle Between Two Walls: The Fiction of J. G. Ballard, finds real world origins for the characters: ‘Leonora Carrington, Coco Chanel, Judy Garland, Nancy Cunard, perhaps an echo of Dorothea Tanning, and Gloria Swanson. ‘Lunora Goalen’, is surely Barbara Goalen, the leading British fashion model of the late 1940s. Another match for ‘Raine Channing’ is Carol Channing, of Hello Dolly (1963) fame and another match is Margo Channing, played by Bette Davis in All About Eve (1950).’

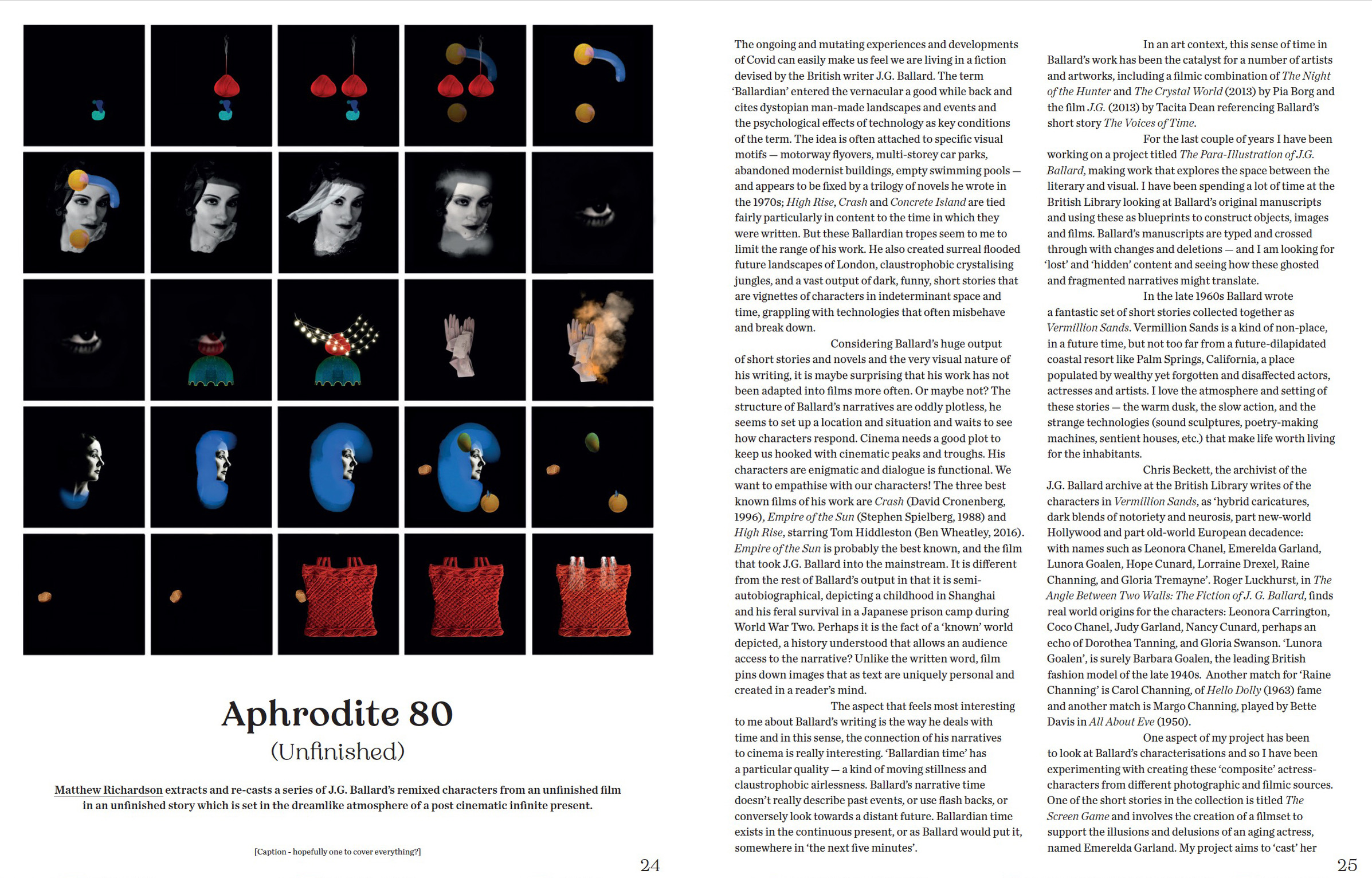

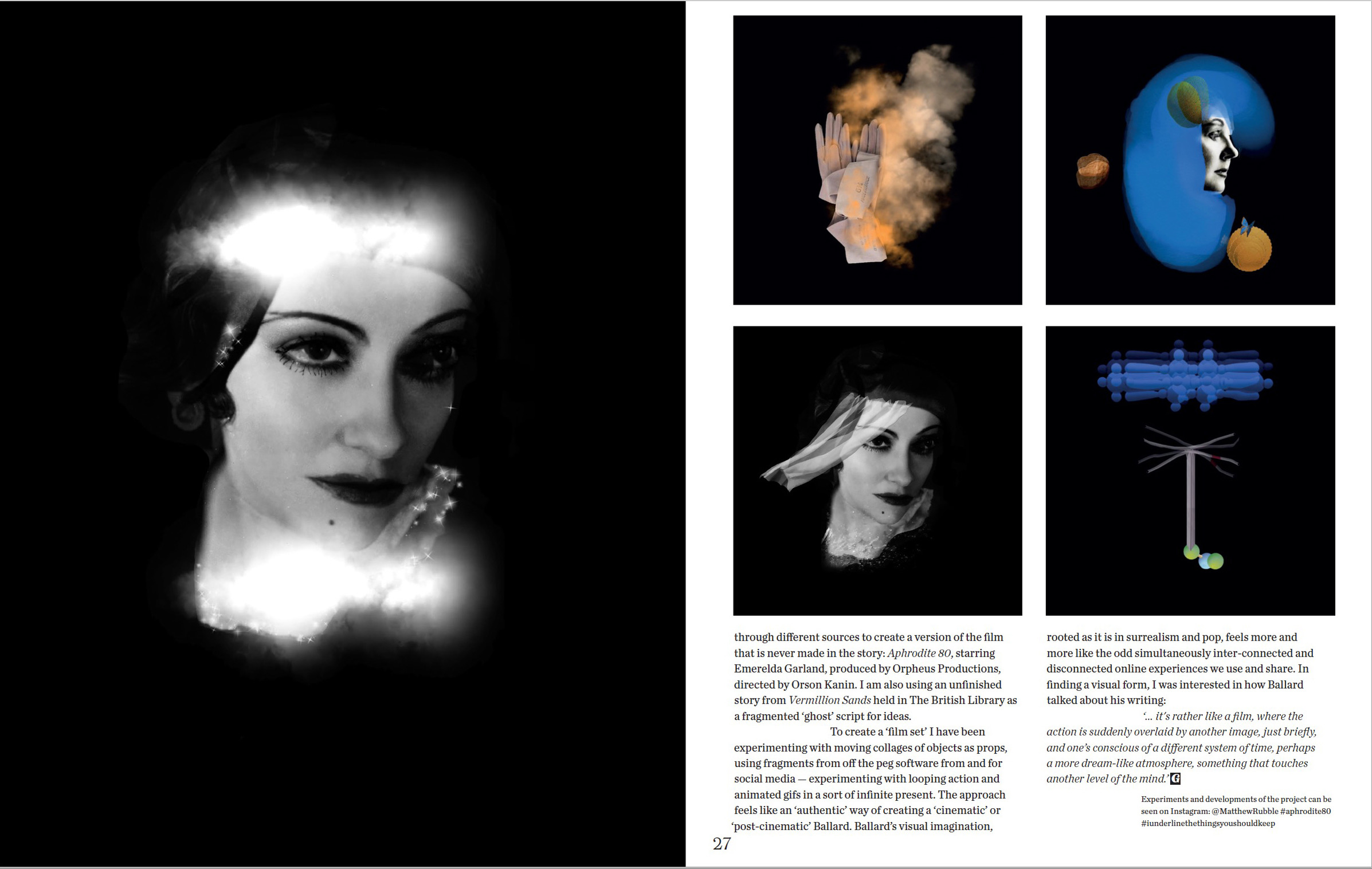

One aspect of my project has been to look at Ballard’s characterisations and so I have been experimenting with creating these ‘composite’ actress-characters from different photographic and filmic sources. One of the short stories in the collection is titled The Screen Game and involves the creation of a filmset to support the illusions and delusions of an aging actress, named Emerelda Garland. My project aims to ‘cast’ her through different sources to create a version of the film that is never made in the story: Aphrodite 80, starring Emerelda Garland, produced by Orpheus Productions, directed by Orson Kanin. I am also using an unfinished story from Vermillion Sands held in The British Library as a fragmented ‘ghost’ script for ideas.

To create a ‘film set’ I have been experimenting with moving collages of objects as props, using fragments from off the peg software from and for social media - experimenting with looping action and animated gifs in a sort of infinite present. The approach feels like an ‘authentic’ way of creating a ‘cinematic’ or ‘post-cinematic’ Ballard. Ballard’s visual imagination, rooted as it is in surrealism and pop, feels more and more like the odd simultaneously inter-connected and disconnected online experiences we use and share. In finding a visual form, I was interested in how Ballard talked about his writing:

‘… it's rather like a film, where the action is suddenly overlaid by another image, just briefly, and one's conscious of a different system of time, perhaps a more dream-like atmosphere, something that touches another level of the mind.’

Experiments and developments of the project can be seen on Instagram @MatthewRubble #aphrodite80 #iunderlinethethingsyoushouldkeep